Raymond Rudorff, The Belle Epoque; Paris in the Nineties (2)

The Moulin Rouge and the Can-can

On October 6, 1889, a new era began for Montmartre as the Moulin Rouge opened its doors for the first time and made the can-can world famous.

The can-can had been born during the Second Empire. It was one of those dances which seemed to resume the gaiety of an age, like the Charleston of the Twenties. After the FrancoPrussian War and the Commune it had survived to a certain extent among the working classes who called it le chahut, a word signifying din and rumbustiousness. Rumbustious the new cancan certainly was. It was not a dance for the elegant and the sophisticated, and one of its first homes was the Moulin de la Galette.

The Moulin was a descendant of the Second Empire bals musettes. A wooden barrier separated the dance floor from rough wooden tables where customers drank the speciality of the house: pitchers of mulled wine. It was certainly not a "respectable" establishment, being an authentic working-class haunt with a public largely composed of working girls and working men on a spree together with an assortment of pimps, prostitutes, petty thieves and local toughs. On week-days it was particularly raffish and more than one underworld feud had been settled by a quick knife blow in the dark streets and winding lanes around it. On Sundays, however, the Moulin de la Galette had a more innocent air of festivity as young apprentices, white-collar employees and their sweethearts came up to the Butte for a sample of popular pleasures and a pleasurable suggestion of low life. Those who danced there did so solely for their own pleasure and occasionally the brassy orchestra would play Offenbach's champagne-light, frothy can-can tunes and the dancers would do their own improvised version of the quadrille with much lifting of grubby skirts and petticoats. This was the chahut-an expression of hilarious high spirits rather like an 1890's version of a "Knees up Mother Brown" in a Cockney pub.

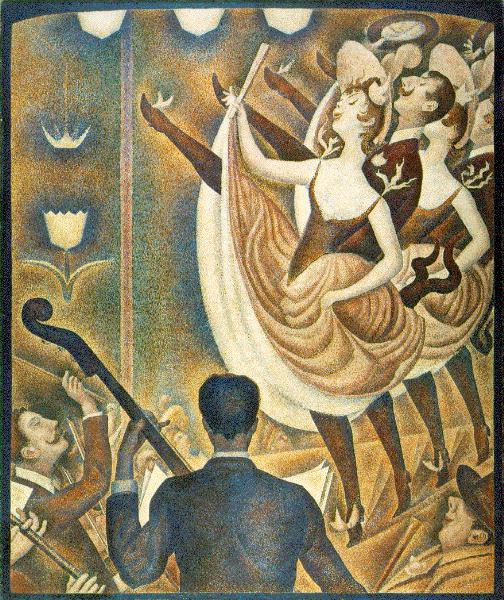

Georges Seurat, Chahut (1889-90)

Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, Poster for the Moulin Rouge (1891)

The chahut was also to be seen at the Elysée-Montmartre, another descendant of one of the many dance halls just outside the city walls. It was no more fashionable than the Moulin de la Galette at first, for when it opened the upper classes of Paris society had not yet discovered the joys of slumming among the dance halls and cafe-concerts of Montmartre. But with its garden where nature was embellished with mock palm-trees made of zinc it had a certain charm. Polkas and waltzes would be danced there to the accompaniment of a brass band and an accordion while an ancient guardian, Du Rocher or "Father Modesty" as he was better known, would stroll among the couples to prevent any excessive immodesty. Ironically enough, it was there that the most immodest of dances sprang out of obscurity.

The band-leader at the Elysée-Montmartre, Dufour, had had the genial idea of reviving the Second Empire quadrille which was a splendid excuse for high kicks and a display of swirling petticoats and knickers which were not always as white as could be desired. The dance was a difficult one for the general public, demanding a high degree of training and great physical agility and assumed the character of a spectacle. It was danced by girls alone, without male partners, and although the basic steps are easy to describe there was much scope for improvisation, depending on the imagination and vitality of the dancer.

As the band struck up, the girls would come out to the centre of the dance floor, start with a few relatively simple steps and then work up to a frenzy, spinning around like tops, turning cart wheels sometimes, and punctuating their gyrations with the famous high kick, the port d'armes ("shoulder arms"), when the dancer would stand on the toes of one foot, holding the other foot as high as possible with one hand. The other main feature of the chahut was the grand écart or "splits" when the dancer would make a spectacular finish by sitting down on the floor with both legs stretched out absolutely horizontally. It was a noisy, stamping dance, it was earthy and animal, performed to a rough-andready clientele in an atmosphere of tobacco smoke, sweat and cheap perfume and, in the person of one dancer known as La Goulue, it became highly erotic.

Another architect of the fame of Montmartre was the impresario Zidler. With his Moulin Rouge, a Parisian attraction became a world attraction. He had begun his working life as a butcher before entering the world of entertainment. In the early Eighties he had sensed that the centre of Paris's geography of pleasure would henceforth be Montmartre and he had realised the possibilities of the revived can-can. There was a vast new clientele to be attracted from the nearby cafe-concerts, cabarets and music halls and he knew that only some good "public relations" work was needed for the tout-Paris and the more respectable public to come to an establishment that would give them the quadrille naturaliste in an atmosphere of authentic Parisian vulgarity. What were needed were new surroundings which would be free of the more raffish public which prevented the socially prominent from frequenting Montmartre. He went into association with the brothers Oller, two leading impresarios, and opened two establishments, the Hippodrome and the Jardin de Paris, but he was not satisfied. What he needed was a new cafe-dance hall in which the chahut would be the main attraction. The "stars" were already to be found at the Elysée-Montmartre: all he needed was a new home for them.

He found his site in 1889: a disused dance hall, the Reine Blanche, with a garden facing the Place Blanche in Pigalle. He called in the painter and illustrator Willette to provide the decorations and it was Willette who had the brilliant idea of crowning the façade of the new building with a giant mock windmill with bright red sails that could be made to turn. The interior had a large dance floor surrounded with galleries where the spectators could sit and drink; in the garden he set up a huge plaster elephant which he had acquired from the Exposition and which contained a tiny stage in its belly. He strung fairy lights between the trees and constructed an open-air extension for the main bar. From the moment when the sails of Willette's windmill began to turn, the Moulin Rouge [Red Windmill]was a huge success. With its curious assortment of attractions, its garden with the hollow elephant in which the belly-dancer Zelaska gave performances, its pastiches of an old Norman cottage and a Spanish palace, the Moulin Rouge had an appeal that drew every social class. At last, the tout-Paris had been given the opportunity to enjoy the "real Montmartre" with no loss of dignity and the delicious sensation of participating in the most democratic of Paris pleasures.

In the meantime, the undisputed star of the Moulin Rouge chahut was La Goulue, who drew the crowds with her own less inhibited version of the dance. In a short time the Moulin Rouge had become the main tourist attraction in Paris. Night after night, the Place Blanche was packed with carriages from the elegant districts of Passy, Neuilly and the Faubourg Saint-Honoré. Hordes of local costermongers and their girls, artisans, shopgirls, clerks, ladies of the town, American and British tourists besieged the hall. . .

This was the great period when for people throughout Paris, France, Europe and the world the Moulin Rouge became a synonym for Montmartre, Montmartre a synonym for Paris and Paris--another word for Pleasure. The Moulin Rouge gave immense impetus to the diffusion of a great erotic myth--the myth of a naughty, free, uninhibited city of frou-frouand champagne, of the wild music of the quadrille which seemed to urge rich and poor alike to forget their cares and live for love and laughter only. Montmartre with its "bohemians", its poets and painters and singers and flaring lights of its gas jets and electric signs exerted a powerful fascination upon the minds of a generation and has continued to fascinate novelists and film-makers ever since.

The reality was more down-to-earth. There was little in common between the lavish imitation of the can-can offered by the modern Folies Bergère and the cinema and the real Moulin Rouge with its not so glamorous ladies who danced with more gusto than choreographic precision. It was a somewhat roughand-ready dance hall with a variety of entertainments including popular songs and music-hall acts. The climax of the evening was when its wooden floor shook under the stamping feet of the dance girls in an atmosphere of smoke, noise and the brassy blare of the band. The girls who performed were not chosen for their looks but because they were strong and their appeal--or rather that of their dancing--was direct, unabashed and crude. There was no false glamour and no barrier of footlights to set them in another dimension from their audience. When the girls came out on to the floor, the audience would surge forward and crowd in upon them for a glimpse of an inch or two of naked flesh. The attitude of many of the spectators was, as one French writer has remarked, more that of the naughty schoolboy than the seeker after eroticism.

There was certainly as much hypocrisy in Third Republic France as there was in Victorian England, but there was also a strongly surviving tradition of public enjoyment of physical pleasures and suggestions. A comparison between English and French popular illustrated journals and newspapers of the time reveals the relative lack of prudery in France and a willingness to enjoy a good, Rabelaisian belly-laugh. Gil Bias Illustré, Le Rire and other papers were full of "sexy" cartoons and jokes about erring husbands, respectable gentlemen caught in compromising situations, wives in bed with their lovers and innumerable advertisements for "rejuvenation pills", cheap contraceptives and treatments for venereal diseases. Humour on the stage was often bedroom humour which might be vulgar but which could also be raised to a high level of comedy and touched with genuine wit. . . .

The Moulin Rouge, c.1900